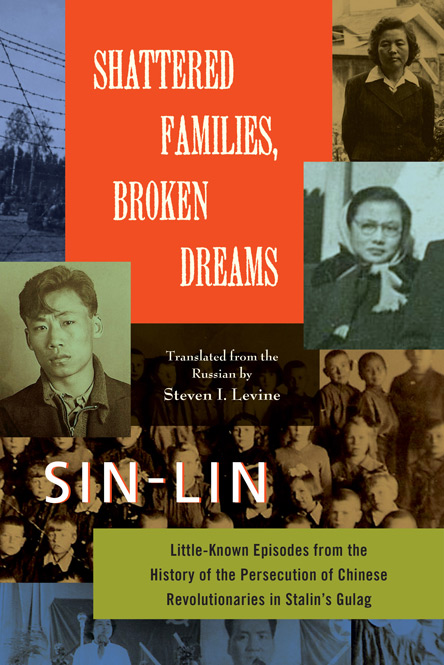

Shattered Families, Broken Dreams

Little-Known Episodes from the History of the Persecution of Chinese Revolutionaries in Stalin's Gulag

Translated from the Russian by Steven I. Levine

Forward by Peter Reddaway

20132, 425 pages • illustrated

ISBN 978-1-937385-18-7 Paper $35.00

ISBN 978-1-937385-19-4 Cloth $75.00

"A compelling, fast-paced, historically enlightening autobiography of a Chinese woman raised in Stalinist Russia along with the children of many Red elite Chinese families which vividly reveals how the cruelties of Stalinism in and out of China made humane relations virtually impossible both at the most intimate level of personal relations and at the highest levels of political power. Important. Illuminating. And a great read."

—Edward Friedman, University of Wisconsin-Madison

"In the spirit of writers like Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Sin-Lin opens a new and almost unknown world for American readers. This harrowing tale of personal trauma and spiritual enlightenment, told with searing honesty and admirable dignity, exposes the endemic cruelty of Stalin's and Mao's Communist regimes and restores its Chinese victims to their rightful place in history."

—Alexander V. Pantsov, Capital University

"Ultimately a story of broken homes, broken promises, broken dreams, and broken lives, [Sin-Lin's] intense account offers fresh insight into the fate of Chinese revolutionaries repressed in Stalin's Gulag and into the insanity of the Great Cultural Revolution."

—Donald J. Raleigh, Jay Richard Judson Distinguished Professor

University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

"Sin-Lin tells the Tolstoyan tale of her struggle to understand her parents, who continued to love each other despite their forced separation, remarriage to other spouses, and political estrangement. They were young Chinese revolutionaries studying in Moscow when Sin-Lin was born. She grew up in a Communist Party boarding school in the Soviet Union and traveled to her parents’ homeland for the first time only as a teenager, several years after her mother had gone back but before her father, who spent years in Stalin’s

gulag before returning to China. The way the Chinese regime abused both of her parents after they came back showed the party’s insecurity about anyone whose loyalties might be divided, even though it was the party that had sent her parents to the Soviet Union to study in the first place. The book includes documents that Sin-Lin gathered much later from Soviet archives about a few of the many Chinese revolutionaries who disappeared into Stalin’s gulag as a result of paranoid power struggles within the communist movement."

— Foreign Affairs

“The history of Sino-Soviet relations serves as the context for this fascinating memoir of a woman born in Moscow in 1937 to parents who were Chinese revolutionaries. Her parents originally met in Harbin as teenagers, and then rediscovered each other in Moscow at the Stalin Communist University for the Toilers of the East (KUTV), as part of the Chinese delegation to the Comintern. Sin-Lin (Xin Ling, “New Decree,” a reference to the 1936 Soviet ban on abortion that ensured her birth) tells her tragic story from several different perspectives, juxtaposing her own memories of life as an orphan at the state-supported “International House” in Ivanovo with the memories of both her mother and father. The reader only learns much later of the circumstances that led to the very different personal histories of Book Reviews 501 Sin-Lin’s parents. Sin-Lin’s mother, Lin Na, unbeknownst to her father, Din Ming, had collaborated with the NKVD before their romance in Moscow. Din Ming was lukewarm to a new NKVD overture concerning intelligence work in South-East Asia (posing as Chinese emigrants), and he was sent to a corrective labour camp a year later. Sin-Lin only met her mother, by then back in China, in 1950 as a 14-year-old, after arriving in China as part of a “Chinese Children’s Delegation.” She struggled with the language and the unfamiliar surroundings and culture, and only learned her original Chinese name from her mother. “’A Soviet person, sing a Russian song!’” exclaimed her new Chinese classmates (p. 22).

Sino-Soviet relations continued to shape the unfolding of this complicated family history, which included new marriages for both the mother and father. By the 1950s, Lin Na occupied important positions as a factory administrator, Party secretary and delegate to the National People’s Congress; Din Ming was released from the Soviet penal system in 1946, and eventually rehabilitated and allowed to return to China in 1955. The mother preferred not to burden Sin-Lin with too many details of her father’s unfortunate history: “The Soviet Union is a great socialist country,” Lin Na explained, “but even there mistakes are inevitable” (p. 62). Sin-Lin’s experience was simultaneously marked by hardship and privilege, in common with other Chinese veterans of Interhouse, some of whom were the offspring of now important officials in the PRC. Their Russian-language skills and familiarity with the Soviet Union were highly valued in the 1950s, and many of them found rewarding

positions in foreign affairs, translation, the press and education. Sin-Lin attended People’s University (built with substantial Soviet support and collaboration) and was invited to join the Communist Party in 1956; she also was sent for “reeducation” to a village in Jiangxi Province after the Hundred Flowers Campaign. In the early 1960s she worked as a translator for the international liaison department of the Central Committee. Years later, in the wake of the further hardships brought by the Cultural Revolution (including the death of her mother in 1968), she translated works into Chinese that illustrated some of the deficiencies and weaknesses of the Soviet system (such as those of Roy Medvedev and Milovan Djilas).

Scholars from numerous fields as well as the general public will find much of interest in this engaging book. The last section includes translated excerpts of Chinese scholarship and Russian archival documents on Chinese revolutionaries in the Soviet Union, including material pertaining to Sin-Lin’s parents (unfortunately all of this material appears without proper archival citations). The Soviet Union, central to Chinese political history since 1949, remains at the centre of her life story. The brutal Kang Sheng, she emphasizes, closely collaborated with the NKVD in the 1930s, and used the violence of the Cultural Revolution to silence people such as her mother who were well aware of this history of collaboration (p. 193). The author chooses not to engage with scholarship that might offer insight into some of the problems she explores, such as the Soviet camp system, deportations and the nationalities, or the history of the NKVD and its relationship to the Comintern and revolution in the East. Several episodes in Sin-Lin’s personal history remain difficult to understand. By 1979 she was mysteriously close to power herself, and CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang apparently served as a patron. She also offers few details about her marriage to Huang Zhuang, who thrived in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, became the Chinese General Consul in Columbia and brought the author to Latin America in the 1980s. Perpetually a victim yet simultaneously well-connected, she emigrated to the United States and acquired citizenship. Translator Steven I. Levine has done a great service in bringing this complicated but intriguing memoir to the attention of an Englishreading audience.”

— China Quarterly

Fighting False Words and Worlds

Jonathan Mirsky

The title of SinLin’s moving, frightening, sometimes disappointing book is incomplete. Her story is also about the way that Chinese Communists lied to themselves while staying loyal to Stalin and Mao, no matter how badly they were treated. Such loyalties are well known, although we can never be reminded of them enough while Mao’s portrait continues to gaze down on Tiananmen Square. Still, SinLin’s main story is, indeed, the plight of Chinese Communists who, before their Party’s victory in 1949, were sent to Soviet Russia at the height of Stalin’s Great Terror; it has hardly ever been told.

SinLin was born in Moscow in 1937 of Chinese Communist parents whom the Party had sent to the Soviet Union, where they married. She tells what happened to them and many other Chinese, adding at the end 242 case histories of Chinese Communists persecuted in the Soviet Union and China that will be invaluable to scholars. The final entry reads simply: “Yaroslavskii Nikolai Andreevich, Chinese name Yang Jinfeng. B. 1898, place of birth: Mukden, China. Shot 4 December 1937.”

Yang was never rehabilitated, unlike SinLin’s father, Din Ming, who after seven or eight years in the Vorkuta concentration camp and further years in internal exile was allowed to return to China in 1955. Lucky to survive the Gulag, he lost his Communist faith. SinLin’s mother, Lin Na (who had several other names), returned to China when her daughter (one of three she bore in the Soviet Union) was an infant, and remained devoted to the Party; but during the Cultural Revolution, after beatings by Red Guards, she was found hanging in a filthy toilet. SinLin does not explain how her mother died.

There is a third story here: of SinLin herself. Until 1950, when she was permitted to return to China with other Chinese children, she was brought up in the Soviet Union, often with the children of muchmarried Chinese Party leaders like Mao Zedong, Liu Shaoqi, Lin Biao, and Zhu De, of international Communists like Eugene Dennis, chairman of the American Party, of Josip Broz Tito, and of Dolores Ibárruri, who in the Spanish civil war was called La Pasionaria.

There, until the war when they starved, “these children enjoyed a life of luxury… cared for and groomed, fed four times a day, and spent all the holidays in the best sanatoriums and children’s camps of the USSR.” More than one hundred Chinese children were cared for at International House, and SinLin considered some of them her brothers and sisters, and her decade there the happiest time of her life. Well beyond the death of Stalin she remained loyal to his memory and once back in China, at school and university, she was teased and sometimes persecuted for being basically Russian. Her mother for years tried to discourage her Russian interests. Her memoir, eloquently translated by Steven I. Levine, a student of Chinese history and politics and a historian of American imperialism, was writtenin Russian.

SinLin’s story discloses overlapping tragedies. As a child in Moscow she had no idea who her father was, much less his fate, and she didn’t know her mother, who had left her behind in Moscow for thirteen years. SinLin reunited with her mother in China, finding that she had three other children and a husband (her fourth by then) who was a pedophile. SinLin learned the truth about Stalin when her father returned to China in the 1950s with his new wife and children. She began to love Mao, joined the Party, married more than once, had children—and learned the greatest lesson needed for survival in Communist societies: to wear an impenetrable mask.

In 1988, after SinLin’s own persecutions and rehabilitations, she managed, with the aid of “MY GOD” (always in caps), to get to the United States. (Although she has not belonged for any length of time to any church, she has said that her God is like the Christian God, but not identical.) Living in Palo Alto, she devoted herself to completing the story of her parents, and on successive trips to archives in Moscow ferreted out the histories and fates of other Chinese Communists in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

A fundamental problem with her book is that much of it includes verbatim dialogue spoken many years, even decades, ago (peasants appear and some of their thoughts are recorded but they never directly speak). There is more verbatim speech of what others had told to those who in turn told their stories to SinLin. Her father’s story is preceded by this troubling sentence: “What follows are my father’s stories told in the first person, supplemented as well with other facts that I learned only after I moved to the United States.” What purports to be her father’s direct discourse and what has been added are not made plain. In many of these narratives, reaching back to SinLin’s childhood, she includes not only her version of the exact words of herself and others but also their gestures and facial expressions of the moment.

I wrote to SinLin about this and she replied: “It was my excellent memory which always distinguished me from my peers. Without my excellent memory I simply could not have written in such detail about this entire history.” She said, too, that her father checked her transcript of his words. I don’t doubt SinLin’s sincerity. But as Oliver Sacks points out in his recent essay “Speak, Memory,”* certainty or sincerity is no guarantee that the memory is accurate. I have decided to trust the overall narrative but remain skeptical about the details.

If one sets aside doubts about the quoted dialogue, what SinLin’s father told her before she emigrated to the US amounts to an utter condemnation of the Chinese and Soviet Communist Parties. Sent by the Northern Manchuria Party Committee, Din Ming arrived in Moscow in 1933 to attend the Stalin Communist University for the Toilers of the East. There he met again SinLin’s mothertobe, whom he had fallen for back in Harbin and whom he would marry. She was already pregnant from one of those liaisons the Party deemed marriages, in her case with Liu Ming, a much older Party member who soon disappeared from her life. According to Din Ming:

She was scarcely seventeen at the time. Liu Ming taught her her first lessons in “revolutionary morality.”

. . . “Girls must give themselves to boys if the revolution demands it. You’ve heard how the old Bolshevik Kollontai propagated the theory of the ‘glass of water,’ that is, she considered that a liaison between a man and a woman is as simple as drinking a glass of water….”

Le Na understood. . . . She submitted.

In 1935 the Comintern Chinese division permitted Din Ming and Le (later Lin) Na to marry. Both were working for the GPU (predecessor of the NKVD), the Soviet secret police. Before long she was told that she might be sent on a mission to Southeast Asia in order to inform Moscow of the situation there. Her husband pleaded with her not to go. A Party official told her they would find her “a better husband” and the state would look after her child. Din Ming was offered a similar assignment in a Southeast Asian country. He refused. “They offered me some sort of clandestine, undercover work that was not for me!” When he refused, Lin Na demanded—this is over seventy years ago—with “puffy, tearstained eyes,” “Din Ming, how could you refuse? All of us must sacrifice our own happiness to achieve the revolutionary goal! This is party discipline!”

When they consulted Kang Sheng, one of the two leaders of the Comintern’s Chinese delegation in the USSR (who later became one of Mao’s principal hatchet men), he told them, just before disappearing into his bedroom and shutting the door, “ALL OF THE NKVD’S ACTIONS WITH REGARD TO THE CHINESE COMMUNISTS ARE CARRIED OUT ONLY AFTER THE AGREEMENT OF THE CHINESE DELEGATION TO THE COMINTERN. This is a secret rule that has been in place in the Comintern.” In 1938 Din Ming was arrested and transferred to the Vorkuta concentration camp. SinLin eventually read in his dossier in a Moscow archive that he had been accused of being “an agent of foreign intelligence” and of “illegally crossing the border from China into the USSR on repeated occasions…. There is no direct evidence implicating Din Ming in espionage activity.”

In 1946 he was released from the Vorkuta camp. In 1955, politically rehabilitated, he returned to China; after some time he began telling his story to his daughter. He said to SinLin:

I thought for a long time about historical justice and cruelty. Do the goals of revolution justify any means, including the murder of innocent people? Was Stalinist terror justified by the building of socialism in the USSR? I myself was now a victim of injustice, and for what?

But both Lin Na and her daughter had come to accept the logic of Communist authority. As SinLin says, writing about the arrest of her mother in 1966 near the beginning of the Cultural Revolution:

I personally believed that the “wise leader” Chairman Mao knew what the party cadres were up to in the lowerlevel party organization, and had decided to put an end to their arbitrary behaviour [by launching the Cultural Revolution against them]. The example I had in mind was my tormentors…. Only after the first three years of the Cultural Revolution [in which both Sin Lin and her mother were brutally persecuted] did it become clear that only a leader who could not control himself could have conceived of inflicting such insults on the entire nation.

The tenacious loyalty to the Party of his exwife and daughter enraged Din Ming. He told SinLin that the bones of the political prisoners who built the White Sea– Baltic canal littered its bottom. “This is what is meant by socalled ‘communist construction.’ …And just who is Stalin? He is a tyrant and a fascist just like Hitler.” When his daughter doggedly attempted to explain that these were “only individual incidents that represent zigzags in the revolution, they cannot eclipse all of socialist construction in the Soviet Union,” Din Ming exploded.

You know too much! Your instructors taught you all of this. They want to make you into a good little girl who knows only how to learn communist dogmas by heart and submit to everything…. I don’t agree with how your mother brought you up. She wants you to be a crystalclear follower of communism…. Why were things so hard for me during my first stretch in prison? Because I was brought up in the same spirit…. I was living on illusions. Now you are just like I was before my arrest.

When SinLin reported this to her mother, she replied, “You are already a Communist, and you must defend your own views…. Had there been no October Revolution would the Soviet Union exist?… Everyone makes mistakes, and we will in the future, too.” Twelve years later she died while being harassed during Mao’s Cultural Revolution.

In 1956, during the Hundred Flowers movement, like many other devout Communists, SinLin made the mistake of trusting the Party’s invitation to criticize it. As she writes, “I had fallen into their trap.” She suggested in a small poster that “it was unnecessary to engage only in praise of the Elder Brother, i.e., the Soviet Union. It goes without saying that what I had in mind was the Soviet army’s suppression of the uprisings in Poland and Hungary.” Then, “the snakes having been tempted out of their holes,” the Party condemned its critics as “rightist elements throughout the country.” SinLin was told by an official: “In concrete terms, you must draw a line in your political relations with your father, from his antiStalinist and antiSoviet views.” The following year she was forced to attack him in writing. In 1958 she was informed that she was now a full fledged Party member, and she married, without any feelings of love for him, a young Party activist who had helped her through her persecution. She was given a job as a translator of Mao’s works into Russian.

What had happened, she writes, referring to her Russian name, was that

The naive, trusting, open, and careless halfRussian halfChinese Lena Din Ming disappeared and in her place was an indifferent, secretive, false Chinese girl Su Linying [SinLin’s Chinese name at the time]…. To ensure that the party members would no longer find fault with her, she declared that she had severed all ties with her father…she began to fill her reports with quotations from Party leaders…she began “to trim her sails to the wind.” … No one knew that inside the Chinese Su Linying there still existed her real self—the halfRussian halfChinese Lena…. And only then did she understand why her mother, starting in her youth, had split in two.

That understanding did not save her from being denounced during the Cultural Revolution and sent with her children to the countryside. At this point her story flashes a light onto what is, after all, the majority population of China: its peasants. There is no verbatim speech here, only misery. SinLin noticed that peasant children the same age as her own were much shorter:

I immediately compared their lives with ours. At least we still had some hope of a future escape from the blind alley in which we found ourselves, but they had no such hope. From time immemorial, from one generation to the next, they suffered in primitive houses…. They ate just once a day throughout the year…. In winter, the adults placed the little children in wooden barrels stuffed with dirty rags and cotton, several children to a barrel, so they would not freeze. The children were in these barrels for several months. I saw how mothers, exhausted by such a life, lifted out of these barrels children who had died from starvation or illness.

In this book of over 450 pages the poor peasants who make up the majority of the Chinese rate one long paragraph. Although the peasants were largely silent, what SinLin tells us about them is one of the most convincing parts of her book.

SinLin learned from her father that what caused his mind to start working again were conversations in the Gulag, often with old Bolsheviks like Ivan Gronsky, once the editorinchief of Izvestiya and Novy Mir. He told Din Ming, “Not a single one of my torturers will die a natural death. History will not tolerate witnesses. Such is the logic of the Stalinist enforcers.” Now safely in the United States, SinLin is such a witness. These days in China it is said that there is “History, and there is Permitted History.” Flawed though it is, Shattered Families, Broken Dreams is the real thing.

—The New York Review of Books